Tag Archive: “books”

Visualizing Publication Timeline

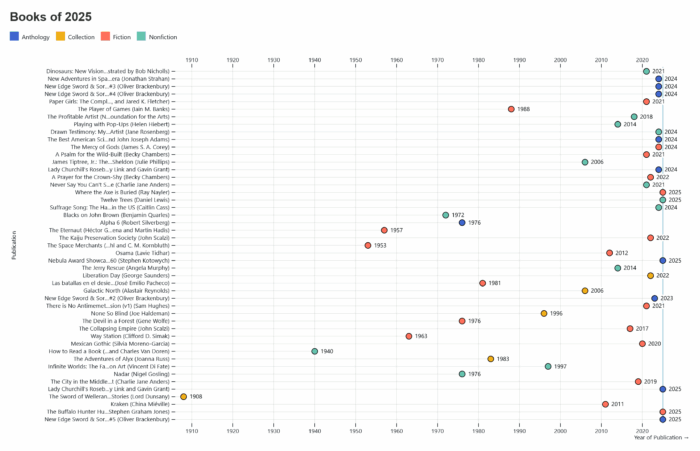

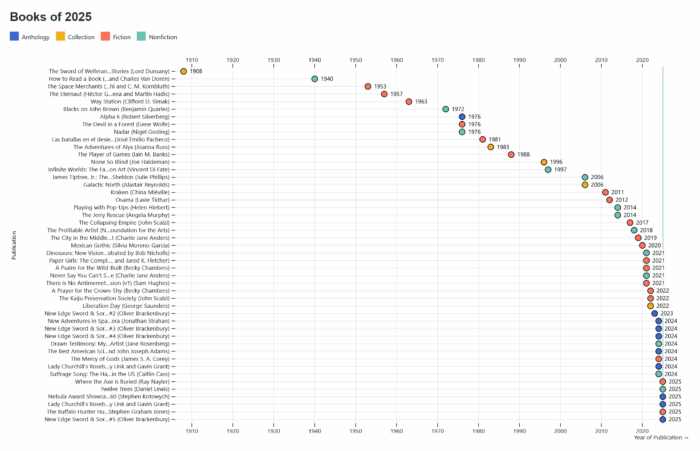

Here is another visualization of my books of 2025. These plots were created with Publications Timeline, an Observable notebook I’ve written as a tool for plotting the publication dates of a list of books or stories. The notebook has various interactive options, but the key use case is visualizing the distribution of items over time.

This example lists books in reading order (click to enlarge):

This is the same list, sorted by publication date:

Posted on Sunday, January 18th, 2026. Tags: books.

Visualizing Books of the Year

My books of 2025 list is complete. In lieu of reviews, here’s an interactive chart to visualize the breakdown. The basic display is a countable bar chart of books by four broad categories. You can split the chart into two or four small multiples by source and/or format. It’s mainly an exercise in creating dynamic charts. Check out the Observable notebook directly for the code and any future updates.

Posted on Thursday, January 1st, 2026. Tags: books.

Books of 2024

Here are the books I read in 2024.

In lieu of more thoughtful reflection, I present a table. I have written paragraph-length comments or summaries for about half of these entries, but I want to proofread, revise, and complete those notes before publishing them. I’ll update this post once I do. (Don’t hold your breath; waiting for myself to get around to completing those notes is the only thing that delayed this post until November 2025, when I finally decided to post it as a list sans commentary.)

Format

- Books are sorted by default in the order I finished reading them. Click column headers to resort according to that data.

- Annotations: Stars indicate books that struck a chord or simply stuck with me. Stars do not necessarily represent recommendations or even superior reviews.

- Attribution: this column names the author or editor (for collections or anthologies). In the case of fully illustrated works the illustrated is also named.

- Category: Books are loosely categorized as novels, nonfiction, collections, or anthologies. I use collection to refer to publications containing multiple works by one author and anthology more specifically to refer to publications containing multiple works by multiple authors. I use those terms here to encompass works like magazines and books of nonfiction essays as well as short stories.

- Links: Title links go to various sources. In some cases, I like to the author or publisher’s promotional page for the book. In other cases, I link to longer reviews, bibliographic entries, or the text itself. Attribution links for most writers of genre fiction go to the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, which blends biography with literary context and opinionated criticism. Otherwise, links to go to the writer’s web site, Wikipedia entry, or whatever reference I can find.

What’s Not Included

- Short stories, essays, or articles. For simplicity, I’m only keeping track of complete books.

- Podcasts. I do listen to a lot of short fiction in podcast form, which merits its own post, but I have not [yet] kept track of episodes.

- Comics. I am including comics in my 2025 list, but I did not track them in 2024.

Books of 2024

| # | ★ | Title | Attribution | Category | Format | Library | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bibliognost: The Lynd Ward Issue | Denis Carbonneau | Anthology | 1976 | |||

| 2 | Afterglow | Grist | Anthology | 2023 | |||

| 3 | ★ | The Best American Science Fiction & Fantasy 2015 | Joe Hill & John Joseph Adams | Anthology | 2015 | ||

| 4 | The Tusks of Extinction | Ray Nayler | Novel | ✓ | 2024 | ||

| 5 | A People's Future of the United States | Victor LaValle & John Joseph Adams | Anthology | 2019 | |||

| 6 | Field Notes on Science & Nature | Michael R. Canfield | Nonfiction | 2011 | |||

| 7 | Orbital | Samantha Harvey | Novel | ✓ | 2023 | ||

| 8 | ★ | Open Throat | Henry Hoke | Novel | ✓ | 2024 | |

| 9 | The Dreams our Stuff is Made Of | Thomas Disch | Nonfiction | 1998 | |||

| 10 | Infomocracy | Malka Older | Novel | Ebook | 2016 | ||

| 11 | ★ | Gideon the Ninth | Tamsyn Muir | Novel | ✓ | 2019 | |

| 12 | Ancillary Justice | Ann Leckie | Novel | Ebook | 2013 | ||

| 13 | ★ | The Knight | Gene Wolfe | Novel | ✓ | 2004 | |

| 14 | Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine #1 | Isaac Asimov, George H. Scithers, & Gardner Dozois | Anthology | 1977 | |||

| 15 | Old Babes in the Woods | Margaret Atwood | Collection | 2023 | |||

| 16 | New Worlds Quarterly #1 | Michael Moorcock | Anthology | 1971 | |||

| 17 | The Riddles of the Sphinx | Anna Schectman | Nonfiction | ✓ | 2024 | ||

| 18 | The Empress of Dreams | Tanith Lee | Collection | Ebook | 2021 | ||

| 19 | I Am Providence | Nick Mamatas | Novel | Ebook | 2016 | ||

| 20 | The Wizard | Gene Wolfe | Novel | ✓ | 2004 | ||

| 21 | Is Math Real? | Eugenia Cheng | Nonfiction | ✓ | 2024 | ||

| 22 | The Book of Flaco | David Gessner | Nonfiction | 2025 | |||

| 23 | ★ | Titus Groan | Mervyn Peake | Novel | 1968 | ||

| 24 | ★ | A Memory Called Empire | Arkady Martine | Novel | 2019 | ||

| 25 | The Nightwatchers | Angus Cameron, illustrated by Peter Parnall | Nonfiction | 1971 | |||

| 26 | ★ | Children of Time | Adrian Tchaikovsky | Novel | 2015 | ||

| 27 | ★ | Return of the Osprey | David Gessner | Nonfiction | 2001 | ||

| 28 | The Three Body Problem | Cixin Liu, translated by Ken Liu | Novel | 2014 | |||

| 29 | ★ | Brasyl | Ian McDonald | Novel | 2007 | ||

| 30 | Lady Churchill's Rosebud Wristlet #48 | Kelly Link & Gavin Grant | Anthology | 2024 | |||

| 31 | The Stars My Destination | Alfred Bester | Novel | 1956 | |||

| 32 | The Book of Barely Imagined Beings | Caspar Henderson | Nonfiction | ✓ | 2013 | ||

| 33 | Bones of the Earth | Michael Swanwick | Novel | 2002 | |||

| 34 | Harrow the Ninth | Tamsyn Muir | Novel | ✓ | 2020 | ||

| 35 | The Future of Life | E. O. Wilson | Nonfiction | 2002 | |||

| 36 | Negative Girl | Libby Cudmore | Novel | 2024 | |||

| 37 | Encounters with the Archdruid | John McPhee | Nonfiction | 1971 | |||

| 38 | A Literary Field Guide to Southern Appalachia | Rose McLarney, Laura-Gray Street, & L. L. Gaddy | Anthology | 2019 | |||

| 39 | ★ | By Force Alone | Lavie Tidhar | Novel | Ebook | ✓ | 2020 |

| 40 | ★ | Some Desperate Glory | Emily Tesh | Novel | Ebook | ✓ | 2023 |

| 41 | The Laws Guide to Nature Drawing and Journaling | John Muir Laws | Nonfiction | Ebook | ✓ | 2016 | |

| 42 | The History of Science Fiction: A Graphic Novel Adventure | Xavier Dollo, illustrated by Djibril Morissette-Phan | Nonfiction | Ebook | ✓ | 2020 | |

| 43 | ★ | Him | Geoff Ryman | Novel | ✓ | 2023 | |

| 44 | ★ | It Can't Happen Here | Sinclair Lewis | Novel | Ebook | 1935 |

Posted on Tuesday, November 4th, 2025. Tags: books, reviews.

Books of 2025

Here are the books I read in 2025. See also my list from 2024 and my visualization of this data.

Table Format

- Books are sorted in the approximate order I started reading them. (Click column headers to sort according to those properties.)

- The “Attribution” column identifies the author, editor, illustrator, and/or translator, depending on the category and nature of the work. There may be one or more name.

- I categorize books containing multiple works by the same author as collections and multiple works by different authors as anthologies. I include complete issues of fiction magazines as anthologies.

- Links are fairly random and subject to change. I link the author name to their website if active, otherwise to their SFE or Wikipedia entry. Some title links go to reviews, which may be more interesting than other references.

- ★ Starred entries indicate highlights I’d like to write more about. In some cases I’ve even scribbled some notes. These aren’t necessarily the “best” books or even my favorites of the year, but it’s a good approximation.

- 👓 Entries marked with a glasses emoji are still in progress. (Anything I started reading before Christmas 2025 appears on this list, even if I didn’t finish it by year’s end; likewise, anything I started on or after Christmas 2025 will appear on my 2026 list.)

Omissions

- Individual short stories, podcast episodes, essays, or articles. I’d like to keep track of the best stories I read online or by podcast, but I haven’t yet. Maybe next year.

- Ongoing or random comics. I check out comics on Hoopla. In some cases I just read one or two sample issues to see if like it. In other cases, I’ll read through back issues and keep up with new issues as they become available – such as with Jim Zub’s various Conan series. I do include a few complete graphic novels in the listing below.

Books of 2025

Posted on Sunday, January 12th, 2025. Tags: books, reviews.

A Limerick, the Throne of the Crescent Moon, and Places in Fiction

Here’s a limerick about Throne of the Crescent Moon, the debut novel by Saladin Ahmed:

There was a wise man from Dhamsawaat

who lived with a boy who prayed and fought.

The man loved an old whore,

who deplored the ghul war,

and the boy met a girl who was not.

(With apologies to Zamia and Raseed for making light of their story – but I suspect Doctor Makhslood would embrace a harmless bit of impious doggerel!)

I enjoy stories with a strong sense of place.

Examples large and small come to mind: sordid New Crobuzon from China Miéville’s Perdido Street Station (not to mention the conjoined cities of The City & The City); Green Town, Illinois – distillate of gothic Americana that it is – from Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes; all of the burgeoning desert planet Arrakis from Frank Herbert’s Dune; and even Redwall Abbey from the Brian Jacques series of the same name.

Vivid impressions of these places root them in my memory.

I think that in the Crescent Moon Kingdoms – and especially the big, bustling, central city of Dhamsawaat – Ahmed may have created a similarly memorable setting. The main character Aduolla Makhslood is an expert ghul hunter and affable old fart who is all the more relatable for his relation to the places he inhabits: his favorite tea house, his run-down neighborhood, and his own dear home. So, as with the examples above, Aduolla’s world has become a part of mine.

(Links to related short stories…)

Posted on Saturday, July 20th, 2013. Tags: books, limerick, reviews.

Eclipse Online recipe

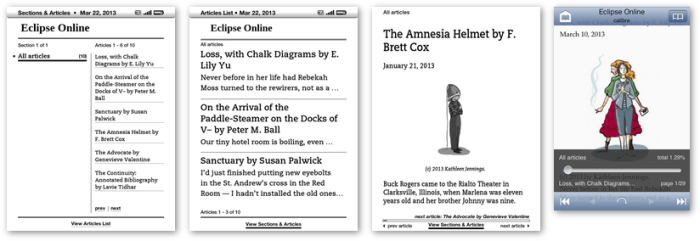

I made a Calibre recipe for Eclipse Online, a free short fiction magazine edited by Jonathan Strahan and hosted by Night Shade Books.

Like Strange Horizons, Eclipse Online is published only as a web site. This recipe assembles an ebook from recent posts and stories. Get more details and the script itself at Github.

Update: Sadly, only a month or so after I discovered Eclipse Online and wrote this recipe, the magazine was closed and will no longer be published.

Posted on Friday, March 22nd, 2013. Tags: books, code, recipe.

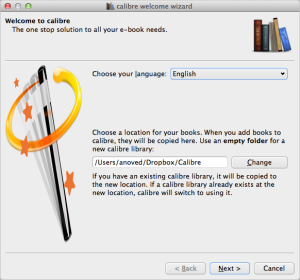

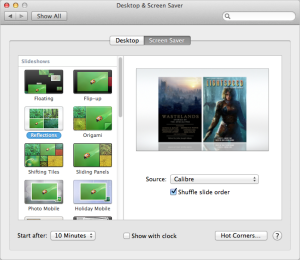

Calibre ebook cover art in Slideshow screen savers

The Mac OS X 10.8.3 update is out. Among the various minor fixes is this item:

Allows the Slideshow screen saver to display photos located in a subfolder

This restores the slideshow behavior from previous versions of Mac OS X; until now, it was inexplicably absent from Mountain Lion (10.8). Missing support for nested folders made it inconvenient to use photo collections organized in folders as the basis for screen savers.

Calibre organizes your ebook files, including cover images, in subfolders of a main library folder. So, now you can select your Calibre library folder as the source for a slideshow screen saver. (If you don’t know where your library folder is, you can re-open the Calibre Welcome Wizard to check the location, as pictured at left above.) The screen saver appears to ignore files that aren’t images, so the result is a slideshow of cover art from your ebook library. This works out nicely if, like me, your ebook library contains many magazine issues with great cover art.

Posted on Friday, March 15th, 2013. Tags: books, mac.

Pinboard bookmarks recipe for Calibre

Here is a script for Calibre which which retrieves your unread bookmarks from Pinboard and compiles them into an ebook. If you use Pinboard to save long articles to read later, and if you like to read long articles with an ereader instead of with your computer’s web browser, this may be the recipe for you. The script is called Pinboard.recipe and you can get it here: github.com/anoved/Pinboard-Recipe (see the Setup section to get started).

This is similar to the Safari Reading List recipe I wrote earlier this year.

Posted on Monday, December 10th, 2012. Tags: books, code, recipe.

Imperative Precautionary Haiku Reviews of the Stories in “Earthmen & Strangers”

I recently picked up a used copy of Earthmen and Strangers, a 1966 anthology of short stories edited by Robert Silverberg. As the cover attests, the book contains “humans and aliens on a collision course – star-studded science fiction.”

In 2010, I posted some haiku reviews of stories I’d recently read. I did some limericks as well. They were all very cheesy, but fun to write. Now I am reviving the gimmick with a new series of haiku reviews. In this post, there is an additional conceit – each bit is phrased as a vague sort of warning to some character or group in the story.

As before, it would be better to call these “synopses” or “selected impressions” instead of reviews. My intent is not to decree whether they have any literary merit, and certainly not to tell you what you should or should not read. In some cases, of course, I can’t help but comment on aspects that would seem out of place if these were written today. The haikus are just a fun record of what I’ve read. Hopefully they give you a taste of what I got from each tale.

Title and author links go to bibliographies at The Internet Speculative Fiction Database.

Dear Devil by Eric Frank Russel

Leave us your poets,

wise passers-by, for who else

might notice hope here.

A Martian artist lingers on ruined Earth, clumsily raising the remnants of humanity.

The Best Policy by Randall Garrett

Listen, my liars –

if cornered by creatures,

the truth will set you free.

Tactful answers to an alien polygraph avert invasion.

Wade among many,

emissary, but risk wanes

your identity.

Rugged individualists from earth make poor company for a little collectivist.

Stand up for yourselves,

women of hot shade and shell;

your men are not gods.

Stranded spacemen help the ignorant natives dispel an abusive cult and seek gender equity. Don’t worry, it’s not a white savior scenario: one of the men is Basque and the other Mohawk!

The Gentle Vultures by Isaac Asimov

Don’t be so hasty,

postwar planet beachcombers,

to assume our doom.

Opportunistic invaders are frustrated by our failure to destroy ourselves.

Stranger Station by Damon Knight

Question the motive

of the gift of elixir –

be tamed and changed by the ichor.

The new human occupant of a lonely trading post prepares for the periodic return of the other party.

I thought this was the most compelling story in the collection. Perhaps it is because the stranger is a truly alien presence: there are no little green men or translator hats here.2

The protagonist suffers from a desperate sense of anxiety and belated revelation as the alien approaches. His urgent effort to understand the purpose of the rendezvous – complicated by the calculated recalcitrance of his computer companion – convincingly depicts what it is like to confront the unknown.

Lower Than Angels by Algis Budrys

Patience, prospector,

lest your raw materials

make too much of you.

A small town sheriff is seduced by a victim’s widow.

Wait, wrong synopsis. This isn’t the NYT best seller list! Here we go:

A scout strives not to deceive the people he meets, but first impressions prove hard to shake.

Blind Lightning by Harlan Ellison

In case of capture,

give courage to your captor.

Release; death; rapture.

A disgraced scientist finds redemption by aiding his aggressor.

Out Of The Sun by Arthur C. Clarke

Behold, a last gasp

is glanced, like rippled glass,

as solar souls elapse.

Astronomers on Mercury see traces of something more than plain old radiation in the radar scans of a short-lived coronal mass ejection.

Some general criticisms:

-

All of the earthmen are exactly that: men. (Not counting the girls abducted to help restart society in Dear Devil.) Women: the greatest alien of all to the men of 1950s science fiction?

-

Many of these stories rely on an automatic communicator or translator device to facilitate dialogue between the titular earthmen and strangers. I think this makes the alien seem more like the merely foreign, with an attendant risk of portraying the aliens as little more than funny-colored people with weird cultures to figure out – or vice versa.

But, more generously, I recognize that the universal translator is a rhetorical device that helps a story advance beyond the mechanics of first contact to a “dialectical” phase where the story’s main ideas can be discussed directly by the characters themselves.

Last but not least, here are physical descriptions of some of the authors, as editor Robert Silverberg saw fit to include in his introductions to their stories:

- Eric Frank Russel is “a towering Englishman”

- Randall Garrett is “a bearded, booming-voiced man”

- Poul Anderson is “a lanky chap of Viking descent”

- Isaac Asimov is “jovial and even boisterous in the flesh”

- Damon Knight is “a slender, soft-spoken man with a deceptively mild smile”

- Algis Budrys “has the general dimensions of an outstanding fullback”

Posted on Wednesday, October 10th, 2012. Tags: art, books, haiku, reviews.