Summer Running Update

After a relatively leisurely winter, I started running in the morning (sometimes early in the morning) this spring. In my experience, running first thing in the morning is a great way to start the day – it wakes you up, and you feel like you’ve already accomplished something by the time you sit down to breakfast. Despite those advantages, I’ve rarely managed to run in the morning on a regular basis until this year, so it has been a worthwhile project.

In early May, I ran in the Binghamton Bridge Run half marathon. It is a flat course through familiar territory. I only put in a week or so of distance training before race, but I was content with the 1:37:57 I managed to run.

On June 16 I ran in the Vestal XX, a pretty hilly 20k race. I ran it last year, too, and was pleasantly surprised to improve on my time by a few minutes, for a 1:33:29 this year. My strategy going in to the race was to “run smarter” – to refrain from going too fast early on in order to avoid running out of energy in the second half of the race, as I did last year. This strategy paid off, and I enjoyed one of the most competitive racing experiences I’ve ever had (moving up in a leapfrog fashion with a small but growing pack) through much of the second half.

I’m not sure what my next event will be, but I’ll post another update here once it happens.

Posted on Saturday, June 30th, 2012. Tags: running.

Weekend Artifact Coda

It’s been a few weeks since I posted a new weekend artifact, so I’ll conclude the series with one more drawing:

Posted on Thursday, June 21st, 2012. Tags: art, weekendartifacts.

Weekend Artifact 15

Drawn with a brush pen thingy.

Posted on Sunday, May 13th, 2012. Tags: art, weekendartifacts.

Weekend Artifact 14

Ballpoint pen sketches.

First, some fútbol doodles – sports photos provide a good reference for interesting poses. Trying to get a feel for the motion in a scene without worrying too much about details.

Second, portraits! Just let the lines spill out and see what happens. You might like it.

Posted on Sunday, May 6th, 2012. Tags: art, weekendartifacts.

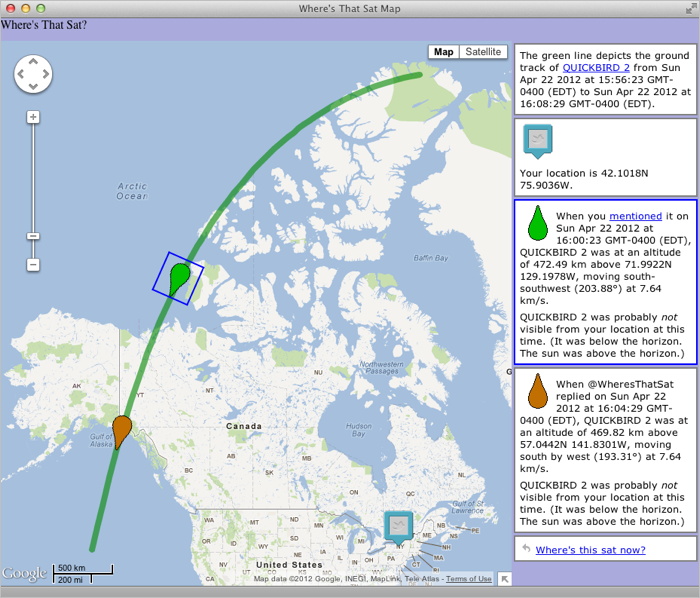

WheresThatSat

My Twitter bot @WheresThatSat is up and running. More information about what it does is available at WheresThatSat.com. In short, it replies to comments about satellites with maps and information about the satellite’s recent course.

Posted on Wednesday, April 25th, 2012. Tags: geography, gtg, wheresthatsat.

WheresThatSat Preview

As I’ve mentioned a few times, I’m making a bot called WheresThatSat which is basically a Twitter interface to Ground Track Generator, my satellite-path-mapping program. The bot responds to queries about satellites (it knows of many – you might even say it has detailed files) by reporting their location at the time they were mentioned.

This week I’ve been making a complementary web site that displays more information (altitude, speed, heading, etc.) along with a Google Map rendition of the satellite’s recent path. The bot will include a map link with each response. The site isn’t finished yet (some icons and styles are still placeholders), but here’s sneak peak:

My goal is to get things working smoothly enough to let WheresThatSat resume running later this week, at least on a trial basis. Although the bot could search for and reply to any mention of the many satellites it knows about, I’ve decided it will only post unsolicited responses to a sample of tweets about one or two “in the news” satellites (queries explicitly addressed to @WheresThatSat will, of course, have access to a full catalog of satellites). This is partly a matter of manners and partly a matter of avoiding excessive API calls (Twitter imposes rate limits on how frequently programs can interact with it).

Posted on Sunday, April 22nd, 2012. Tags: geography, gtg.

Time Lapse Portrait

Here’s another time lapse portrait drawing:

I like this video orientation better, but I realize it’d probably be better if the camera wasn’t quite so close to the page. Frames are five seconds apart, so the whole thing took four or five minutes.

Click here to see the final sketch.

Posted on Sunday, April 22nd, 2012. Tags: art, timelapse.

Weekend Artifact 12 and Other Sketches

Haven’t done this in a while – here’s a left handed drawing:

Here’s Herschel Walker, from this Air Force photo:

Click here for more drawings from earlier this week.

Posted on Saturday, April 21st, 2012. Tags: art, weekendartifacts.

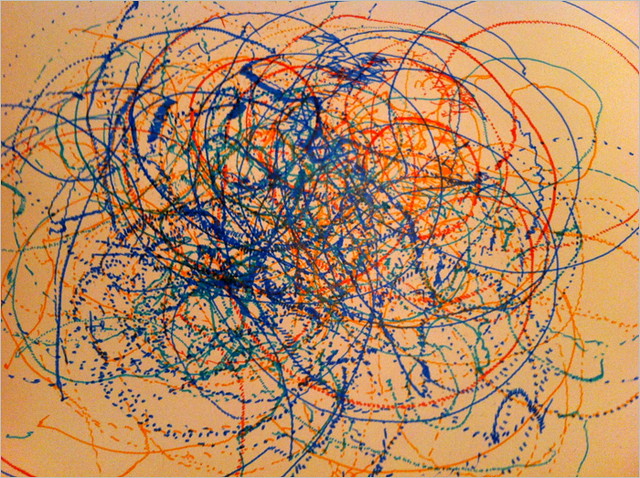

Weekend Artifact 11: Windup Artomaton

I don’t do abstract art. I have robots do it for me.

Inspired by the milk frother drawbot recently featured at The Kid Should See This.

Posted on Sunday, April 15th, 2012. Tags: art, weekendartifacts.