Chipmunk Basic

Playing with Chipmunk Basic is a decent way to learn about programming.

Most of this content is now mirrored at https://github.com/anoved/Chipmunk-Basic-Stuff.

Documentation

I made a framed, cross-referenced HTML version of the standard Chipmunk Basic documentation. View it here. (Documentation may not be up to date.)

Examples

- Simon Says – a simple game

- HTTP Content Retrieval – using sockets

- Rendering Shapefiles – reading & rendering complex file formats with Chipmunk Basic

- Vintage Examples – fragments of old visual cbas programs

Syntax Coloring Extensions

Edit your Chipmunk Basic code in style with these syntax coloring extensions for a variety of excellent text editors. “Syntax coloring” draws recognized language commands and control statements in different colors.

These extensions do not recognize many elements of the Chipmunk Basic language (such as most of the Mac-specific capabilities described in the Quick Reference). Consider these extensions a starting point that you can add to and improve as needed.

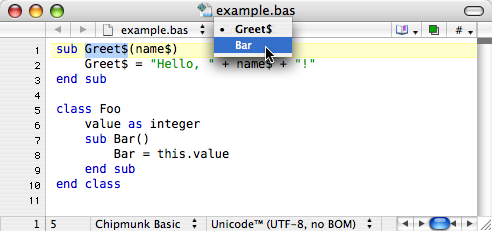

TextWrangler/BBEdit

Download Chipmunk Basic syntax module for TextWrangler 2.2+ [2k .zip]

Rudimentary syntax module for TextWrangler 2.2 or BBEdit 8.5. Put the plist file in your ~/Library/Application Support/TextWrangler/Language Modules folder. Named subroutines are listed in the function popup menu.

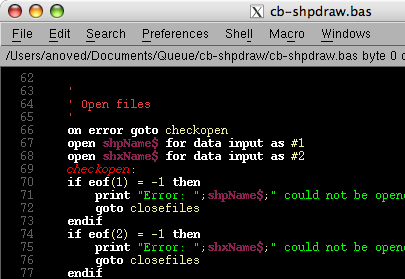

NEdit

Download Chipmunk Basic syntax recognition configuration for NEdit [1k .nedit]

Syntax pattern recognition configuration for the X11 text editor NEdit (roll your own?). Save and integrate with your NEdit configuration file using the command nedit -import cbasne.nedit, then select Save Defaults from the Preferences menu.

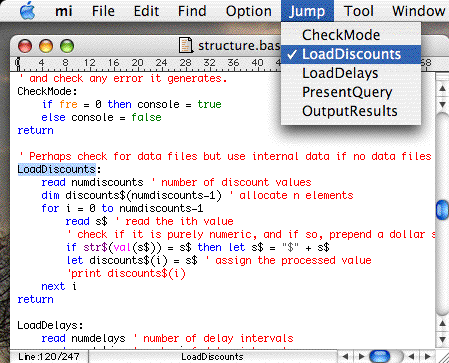

Mi

Download Chipmunk Basic syntax color mode for Mi [6k .zip]

Chipmunk Basic syntax mode for the text editor Mi. Put the expanded folder in your ~/Library/Preferences/mi/mode/ folder. Recognizes files, basic keywords, named subroutines and gosub labels.

Commands & Techniques

Note: These notes are based on an old version of Chipmunk Basic.

fseek

This statement lets you navigate around an open file.

fseek #FNUM, POS

FNUM should be an open file; the file position marker is moved to byte number POS (where 0 is the first byte in the file). I don’t know if there is a way to determine the total length of a file without reading through it until it hits eof. I do not think fseek accepts any aditional arguments, such as a “seek set” value indicating where to seek from, so POS is always relative to the beginning of the file.

This can be used for more “random” file access than is possible with the open "filename" for random as # construct, which is really most useful with a regular record format. With fseek you can “fast forward” or “rewind” through a file by an arbitrary number of bytes.

memstat()

The memstat function reports the internal state of Chipmunk Basic:

>memstat()

Copyright 1994 Ronald H. Nicholson, Jr.

Chipmunk BASIC v3.6.2(b6) current filename:

variables = 84 variables2 = 0

arrays = 0

program = 0 tokens = 0

stack = 0 stack2 = 0

loops = 0 loops2 = 0

memory used = 84 exec level = 1

mem avail = 20971520 zone size = 0

>

merge

You can include code with the merge statement.

merge STRINGEXPR

Chipmunk Basic has a merge command which loads the specified program file’s lines into memory. Unlike the load command, the current program, if any, is not closed before merging. This allows code from multiple files to be loaded simultaneously.

merge can be used from the Chipmunk Basic command line to combine code from two files, but it can also be used within a program to embed code from another file!

Lines from the merged file are inserted into the current file according to line number. If you write code using line numbers, be careful to anticipate this, or else lines from the merged file may overwrite lines in the current file. Otherwise, merged code is appended to the end of the current file. In other words, if all the code is unnumbered, merged files are numbered starting at the end of the sequence used for the parent file.

What this means is that merged code will not necessarily be executed when it is merged, which may be unlike the behavior of similar commands in other languages, such as C’s #include or Perl’s

require. You could approximate that behavior with carefully crafted line numbers, but appending is perfect if you use merge to include subroutines implemented with

gosub labels or sub.

Command Line Arguments

Here is an example of a short cbas program that counts and displays any arguments that are passed to it on the command line. This program illustrates use of the #cbas#run_only directive and the argv$ string.

The #!/usr/bin/basic line tells the shell what program to use to interpret the rest of the file, and the #cbas#run_only line directs the interpreter to quit once the program is finished running.

#!/usr/bin/basic

#cbas#run_only

num_args = len( field$( argv$, -1 ) ) - 2

print num_args ; "arguments"

for i = 3 to num_args + 2

print " argument ";str$(i-2);": ";field$(argv$,i)

next i

Once made executable (chmod +x prog), this program will print the number and content of the arguments it was called with, as shown below. (“>” is the shell prompt.)

> chmod +x prog

> ./prog

0 arguments

> ./prog Hello, you!

2 arguments

argument 1: Hello,

argument 2: you!

> ./prog 8 23 option-A option-B

4 arguments

argument 1: 8

argument 2: 23

argument 3: option-A

argument 4: option-B

In addition to your actual arguments, argv$ contains the name of the interpreter and the name of the program file being run. So, the full content of the argv$ string for the last example above is:

/usr/bin/basic ./prog 8 23 option-A option-B

Giving field$ negative one as a field index causes it to return an arbitrary string with a length corresponding to the number of field separators (space by default) in its input. Chipmunk Basic appears to append an additional space to the argv$ string. This means that len(field$(argv$,-1)) returns the number of real fields (arguments) in argv$, which is reduced by two in the example above to ignore the ever-present interpreter and program name arguments.

sys()

Whatever string you provide to the sys function will be passed to the shell and executed as a shell command. To the best of my knowledge, anything you can do at the command line prompt you can do through the sys function (the challenging part might be working with the results; the cbas docs say that sys returns the exit status of whatever you

called, but that may not always be what you’re looking for). At any rate, it is a powerful function.

~> basic

Chipmunk BASIC v3.5.8b7

>sys("pwd; ls")

/Users/anoved

Desktop Library Music Public

Documents Movies Pictures Sites

>

Starting in my home directory, I invoked the cbas interpreter and passed the command string "pwd; ls" to the sys function. The current working directory (/Users/anoved) is printed by pwd and the contents of that directory are

printed by ls. This all happens without exiting the basic interpreter; notice that the prompt is still the basic prompt after the shell commands have been executed. This illustrates how other programs can be called from within cbas.

You could even write specific components of a cbas project in a different language, and encode return information in the exit status of those sub-programs.